Is Scotland’s oil industry still a good career option?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOil made austere Aberdeen rich and the frigid North Sea port could not hide its wealth forever.

At first, straight out of Texas, the bars were filled with big hats, high heels and flash wheels.

Young men began to drive Porsches, their bosses bought Aston Martins.

The granite sparkled in the sunshine.

Sarah Browell-Hook, who grew up in the booming city says she took it all for granted.

“Everybody worked in the oil industry,” she says.

But nothing lasts forever. The average annual price of Brent crude – the North Sea benchmark – peaked in 2012 at $112 per barrel. By 2014, the year of Scotland’s independence referendum, it had fallen to $99 per barrel.

The price then slumped to $52 in 2015 and $44 in 2016, a shock which led to mass redundancies in the North Sea – some 20,000 jobs lost between 2017 and 2018 alone – and a collapse in tax receipts for the UK Treasury.

“Everybody knew somebody who’d been made redundant and been affected,” said Ms Browell-Hook, a 36-year-old mother-of-two who had never worked in the industry herself.

The slump prompted her to make a decision, to start a second career in decommissioning, dismantling the rigs and pipelines from which Aberdeen prospered.

“The oil boom and what it brought to my family was that my dad provided for his family comfortably and I guess the end of that journey, I’m hoping that the decommissioning side of things can help me provide for my family and for my children,” she says.

The collapse in the oil price was a blow to the credibility of the Scottish government which, four months before the 2014 referendum, had predicted tax receipts in 2016/17 from oil and gas would be between £2.9bn and £7.8bn.

Opponents of independence, who had prevailed in the referendum by 55% to 45%, said such dismal figures proved that a sovereign Scotland would have started life in crisis.

Independence campaign

Of course that was then and this is now but are we really at the end of the journey?

In Dyce, a suburb of Aberdeen, the Spider’s Web is bustling. The pub sits next door to the city’s heliport and is known as a waiting room for offshore workers.

It’s nearly lunchtime and the place is busy with oilmen – they are all men – savouring their first beer after two or three weeks on the rigs.

There is a lot of talk of wives and girlfriends, of the balance between the reward of another pint and the risk of missing the train home.

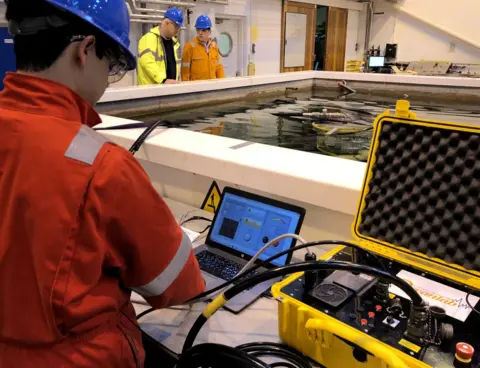

Here views about the sustainability of the industry are mixed. One oil worker, who did not want to be identified, fretted about climate change and the need, as he saw it, to diversify away from fossil fuels for the good of the planet.

And yet there is still temptation below the waves.

New fields

One drinker, Russell Edwards, 51, says for some people in the pub, decommissioning is a dirty word.

“They are finding more fields,” he says. “Exploration is becoming more sophisticated.”

He hopes the industry will see him to retirement but as for someone starting out now, “who knows?”

Confidence is to be found, as so often, behind the bar where Lauren Grant, 23, is pulling pints. She has worked at the Spider’s Web for five years but now she is heading offshore herself, embarking on a career in oil exploration.

“I think there’s a good bit more time in the North Sea,” says Ms Grant. “I’m a local girl trying to get into our local industry.”

After growing up in Dyce, watching the helicopters fussing to-and-fro, and studying geology at Aberdeen University, she is now about to take the plunge.

“Things are definitely on the up,” she says.

And is she looking forward to stopping off in the Spider’s Web for a pint when she comes ashore?

“Absolutely,” she says, “can’t wait.”

Source link