The female physician who popularised the Pap smear

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontThe daughter of a former slave, Helen Octavia Dickens empowered teen mothers and pioneered the popularity of the Pap smear, helping to save hundreds of lives.

In 1951, a 31-year-old mother-of-five walked into Maryland’s Johns Hopkins Hospital for what she called “a knot on my womb”. The knot, it turned out, was a virulent cancer that had started in her cervix. She would soon die in agony of the disease, then the number one killer of American women.

If Lacks had been given a Pap smear, she may have survived. Developed a decade earlier, the simple screening tool – named after its creator, Greek gynaecologist George “Pap” Papanicolaou – was the newest and most promising technology in early cancer detection. It rose to become the gold standard in cancer screening, and would be instrumental in slashing cervical cancer rates by 70% over the next half century.

But its benefits were not applied equally. In the 1950s United States, the face of cancer prevention campaigns was a well-to-do white woman; reproductive cancer in black women was all but invisible. (Even when the magazine Colliers told the story of Lacks, whom they called “Mrs L”, they pointedly left out her race.) Far fewer black women got the test, either because their doctor never offered it or because they didn’t know to ask.

Yet at the same time that Lacks’ tumour was growing, a gynaecologist named Helen Octavia Dickens was driving around Philadelphia in an American Cancer Society van, giving black women free Pap smears. She parked her van at local churches, and invited women to come inside for what she described as “a painless, simple, five-minute procedure”. Many times she found cancer and was able to operate, turning those patients into lifelong devotees.

Getting them to enter the van, however, was no small feat. Besides the silence surrounding cervical cancer, Dickens had to overcome a deep and well-founded distrust of the US medical system. Black women, she knew, had good reasons to be wary of getting a pelvic exam from a (usually) white male doctor. These fears went back to James Marion Sims, the Southern doctor dubbed the “father of modern gynaecology,” who purchased enslaved black women suffering from fistulas to experiment on in the days before anaesthesia.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesDickens worked to allay black women’s fears of medical experimentation and forced sterilisation by emphasising the benefits of the test in preventing cancer, then called “the dread disease”. “If every woman in Philadelphia had a Pap test once a year, no woman need die of uterine cancer,” she told the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1968.

She saw her anti-cancer work as a form of racial progress that would strengthen the black community and counter the inadequate healthcare they were receiving in Jim Crow America. Historian Meg Vigil-Fowler, who wrote her thesis on early black women doctors in America, sees Dickens and other black women physicians of her era as “medical missionaries”.

“As dedicated as they were to becoming physicians, a dedication to the health of the black community in general was the paramount thing in their lives,” Vigil-Fowler says. “And becoming a physician stemmed from that.”

In pursuing that goal, Dickens tried not to spotlight the tremendous challenges she herself had faced as a black woman in medicine. “She didn’t want it to be a thing,” says her daughter, Helen Jayne Brown, a doctor in Philadelphia. “She just thought she had to move forward and not let it bother her or get to her.”

But her very existence in a field dominated by white men – a field that was forged on the bodies of enslaved black women – made its own quiet statement.

‘I didn’t see why I couldn’t do it’

Dickens was born on 21 February 1909 in Dayton, Ohio. Her father, Charles Warren Dickens, had been an enslaved child and water boy during the Civil War. He was nine when the war ended, newly freed but with few prospects. He taught himself to read by asking people on the street the meanings of words, and took his name from the well-known English novelist, whom he once met in person. But the racism of the era confined him to life as a janitor.

Her mother, Daisy Jane Dickens, worked as a domestic servant. Though her father insisted that his wife be a homemaker when they married, he encouraged his daughter to become a nurse. Dickens, meanwhile, had other ideas. “I got it into my head that if I were going to be a nurse, I might as well be a doctor,” she said in a 1988 oral history interview with the Black Women Physicians Project.

Dickens had never met a woman doctor, black or white. Nevertheless, “it was what I wanted to do and I didn’t see why I couldn’t do it”, she would say. Though her father died of a dental infection when she was eight, her mother kept his dream of education alive.

Courtesy of Helen Jayne Brown

Courtesy of Helen Jayne BrownThe path to medicine would not be easy. But by going to night school and summer school, Dickens managed to graduate high school at 17 and gain entrance into Crane Junior College, a tuition-free city college in Chicago where she took premedical courses. To meet the Illinois residency requirement, she moved in with her aunt and worked occasionally at the local A&P Grocery to get by.

In interviews, she recalled her strategy for ignoring the racism she encountered in the classroom. In every lecture, she immediately sat in the front row. “If other students wanted a good seat they had to sit beside me,” she said. “If they didn’t, it was not my concern because I could clearly see the professor and the blackboard as I was right up there. This way I didn’t have to look at them or the gestures made that were directed against me or toward me.”

But although she studiously avoided prejudice, prejudice found her. It was in applying to medical school, she recalled, that she first felt the burden of being both black and a woman. That’s when she learned that many schools did not accept female students, while others didn’t accept black students. She would later say that “the Negro woman had a double handicap – her race and her sex”.

Kutcher Studios/University of Pennsylvania

Kutcher Studios/University of PennsylvaniaIt was a particularly bad time to be a black woman entering medicine. In the segregation era after the Civil War, women’s colleges and black colleges, despite their shoestring budgets, were crucial to training these doctors. But by 1900, the tide was turning against them. Medicine was consolidating its power as a field based in scientific research, dominated by white men. By 1920, the year women won the vote, most of the women’s colleges and all but two of the black colleges had shuttered.

The black schools that remained would enact quotas for women – which is likely why Dickens didn’t get into her first two choices, Howard University in Washington, DC and Meharry Medical School in Tennessee. Meanwhile, many women’s schools “distinctly did not want coloured students… the difficulties which they threw in the way of coloured girls are almost inconceivable”, wrote civil rights pioneer WEB Du Bois in his 1933 article “Can a Coloured Woman be a Physician?”

Caught in the double bind of racism and sexism, the numbers of black female medical students dwindled. In 1920, Vigil-Fowler identified just 20 black women medical school graduates, compared to 47 in 1900. (The true numbers may have been slightly higher, given that medical school records did not always list students by race.) The number of black women doctors actually practicing in the country at that time, according to historian Darlene Clark Hine, was 65.

Dickens ultimately attended the University of Illinois Medical School with a state scholarship, which paid her tuition fees of $165 per semester (around $2,500 or £2,000 today). There, she encountered racism not just from students but from her teachers. After one professor made a racial slur, Dickens and the other black students walked out of class and never returned.

In 1934, she graduated as the only black woman in her class of 175 students. In her class photo, white men in jacket and ties surround her on all sides. Chin high and hair neatly coiffed, she looks directly into the camera, as if daring anyone to question her right to be there.

Gibson Studios/University of Illinois at Chicago

Gibson Studios/University of Illinois at ChicagoVanessa Northington Gamble, a historian of US medicine at George Washington University, remembers how she too was made to feel that she didn’t belong as a black woman in medical school. Gamble, who attended the University of Pennsylvania’s Medical School in the 1970s, was one of Dickens’s mentees. When she shared her experience with her mentor, Dickens told her that she had survived similar treatment. “From where I came from to where I am now, I knew I had to be better than they,” Dickens told her.

“She had a certain pride,” says Gamble.

Medical degree in hand, Dickens now faced an even steeper hurdle.

Starting in the 1910s, state laws began requiring doctors not only to graduate but to complete a clinical internship at a recognised hospital. At the time, few hospitals accepted black or female residents. Of those that did, black hospitals tended to fill their positions with black men, while women’s hospitals preferred white women, writes historian Ruth J Abram. Black women were left to compete over the few spots that remained.

Isabella Vandervall, a 1915 medical school graduate, was one aspiring doctor caught in this bind. “For many years the coloured woman physician has practiced and prospered,” she wrote in 1917. But with the internship requirement, “a huge stumbling block, one which seems almost insurmountable, has suddenly been placed in the path of the colored woman physician”. Vandervall finally secured an internship at a New York hospital – until they realised she was black, and sent her home.

Dickens too hit this stumbling block. She was eventually accepted for a residency at Provident Hospital, one of the first black-owned hospitals. A small, 200-bed affair, Provident served mainly black residents of the impoverished South Side of Chicago.

Whereas male residents lived in the intern quarters within the hospital, female residents had to share the nurses’ quarters one block down the street. This meant they often had to run over at night to deliver babies. Still, “if you wanted the job, you just took it as it is”, Dickens would recall. “This was true for black women and white women.”

After two years treating tuberculosis and delivering babies, Dickens was “very anxious to go into the community,” she recalled. That chance came in the form of a notice on a bulletin board. A Philadelphia doctor named Virginia Alexander was looking for a female resident who had “social vision” and could “fit into my project for community health”.

University of Pennsylvania University Archives Image Collection

University of Pennsylvania University Archives Image CollectionAlexander, a black Quaker, had seen that there were no places in her city dedicated to poor mothers. She began treating patients out of her home, a three-story row house, eventually expanding it into a three-bed hospital called the Aspiranto Health Home. Alexander not only delivered babies but instructed new mothers on proper child care, gave them birth control, and provided a safe place for family to visit. She described her project as “socialised” medicine.

“She always considered it an antidote to the racism that was current in Philadelphia’s hospitals at the time, so that people would be treated with dignity and respect,” says Gamble, who is writing a biography of Alexander.

Dickens packed her bags and came to work with Alexander. Once again, her patients were poor and largely black. Once, she arrived at the home of a woman in labour to find that there was no electricity, and had to move the bed to the window to conduct the delivery by streetlight. Meanwhile, Alexander “had no idea of money at all”, Dickens recalled; sometimes she would treat a whole family and charge them $3 (around $50 today).

After one year, Alexander left Aspiranto to become the first black student at Yale’s School of Public Health. Now, at 27 years old, Dickens became head doctor of the birthing centre – as well as assuming care of Alexander’s father, who lived on the building’s third floor.

Over her seven years directing Aspiranto, Dickens became a well-known fixture in the community, speaking at churches and working at well-baby clinics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1943, dedicated to what she called “the care of women”, Dickens too returned to school to get a masters in science in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Her training coincided with the birth of a new technology that would help define the second half of her career: the Pap smear.

By the end of World War Two, doctors were searching for a weapon to end a different kind of struggle: the war on cancer. Enter the Pap smear. In this simple test, a doctor brushed off cells from the cervix, placed them on a glass slide, and examined them under the microscope for swollen or fragmented nuclei, which suggested cancer or potential cancer. The Pap smear held the tantalising promise that science could stamp out cancer before it even technically existed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDickens saw the Pap smear as an opportunity to change this lopsided narrative and prevent thousands of needless black deaths. She framed her aim in terms of racial progress. “It is necessary that expectant mothers have early and adequate pre-natal care in order that we may build a race physically strong and free from disease,” she told the Philadelphia Tribune in 1946.

Her cancer crusade overlapped with a slew of accomplishments and accolades in her professional life. That same year, after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, she became the first certified black female gynaecologist in Philadelphia. In 1948, she was appointed the first female head of the obstetrics and gynaecology department at Philadelphia’s Mercy Douglass Hospital. In 1950, she became the first black female fellow of the American College of Surgeons.

In the meantime, she had met and married another resident, Purvis S Henderson. Out of necessity they began a commuter’s marriage: Henderson returned to his surgical practice in Savannah, Georgia while Dickens completed yet another residency at Harlem Hospital in New York. After reuniting in Philadelphia, the pair raised two children, one of whom would ultimately follow in her mother’s footsteps.

Courtesy of Helen Jayne Brown

Courtesy of Helen Jayne BrownDickens’s first order of business at Mercy Douglass was to establish a dedicated center for cancer prevention. She hired a cytologist (a specialist who analyses cells under the microscope) a black woman named Willa Mae Flowers who had trained with Papanicolaou, to read the smears – a feat requiring “meticulous scrutiny”, according to Dr Pap himself. Then she began collecting data on how often black women got cervical cancer, using her findings to combat national misconceptions about cancer rates and win funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Dickens was instrumental in spreading the Pap smear to doctors’ offices across Pennsylvania. By 1965, she had had trained more than 200 black physicians how to perform and interpret the test. She also empowered women to take matters into their own hands. Her signature contribution was forming a bridge between civil rights organisations, women’s clubs, and the medical community, writes Ameenah Shakir, an assistant professor of history at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, in an article on Dickens and medical citizenship.

Many women chafed at the idea of getting a pelvic exam, either from fears of the doctor or from embarrassment. Cervical cancer in particular held a whiff of promiscuity: when Lacks was initially diagnosed, doctors pointed her to the venereal disease clinic, thinking her cancer was likely caused by syphilis. Dickens herself often said that cervical cancer was rare among nuns and frequent among prostitutes.

In women-only groups, Dickens overcame these concerns by keeping her language vague, using terms like “cancer of women”, Shakir writes. Dickens suggested that each family appoint a female ambassador to ensure that all women relatives had their Pap smear. A board member for the American Cancer Society, she lobbied the group to create pamphlets featuring black women and suggested that their films show black women getting Pap smears and going on to have children, to counter fears of sterilisation.

Her techniques worked. In 1965, she drew a crowd of 250 women to St Charles Borromeo Hall Parish in South Philadelphia to receive Pap smears. By 1975, reported cervical cancer deaths in black women were 16 out of 100,000 – a third of what they had been in the 1930s.

Still, that number was twice the rate it was for white women.

In her medical training, Dickens also witnessed another phenomenon that was devastating women, both black and white: laws criminalising abortion. At Harlem Hospital, she worked in a septic abortion ward for women who had gotten – or given themselves – botched abortions. The experience pained her deeply.

“I just felt that these women deserved to be taken care of, just like anybody who comes in with anything,” she would recall. “And I certainly (didn’t) want to see those complications again.”

University of Pennsylvania

University of PennsylvaniaIn the 1960s, it was still illegal in many states to provide the contraceptive pill to unmarried women. But in 1967, after joining the faculty of Penn’s Medical School, Dickens opened a teen obstetric clinic, teaching teenagers how contraception worked and urging many to get on it. By 1970, 40 out of 50 teenage girls she counseled and tracked had started using contraceptives.

Dickens surrounded young mothers-to-be with a cohort of their peers and supported them with a social worker, a family planning counselor, a nurse, and a “male outreach worker” who encouraged fathers and new husbands to participate. She provided classes on childrearing and gave mothers-to-be tours of the hospital birthing ward to allay their fears about the birthing process. There were theatre productions, dance classes, and visits from a beautician.

Most importantly, at a time when many schools forbade pregnant students from attending class, she encouraged these girls to stay in school or to return after giving birth. “She believed that these young women had futures, and her having this clinic was a way of telling them that,” says Gamble, who shadowed Dickens in her work with teenaged mothers when she was in medical school.

As always, Dickens did this work quietly. Her strategy fits into the way that many women physicians in that era practiced reproductive health as activism, says Jacqueline Antonovich, a historian of medicine and gender at Pennsylvania’s Muhlenberg College. “Women just sort of did the work but weren’t really loud about it,” she says. “The best way to be political was to do just do the work.”

Brown, Dickens’s daughter, has another theory for why Dickens was able to fly under the radar. “No one was really paying attention to black women and their lifestyles and their concerns,” she says. “And so because her practice was largely African-American, she could teach and do and say whatever she wanted to. And what she wanted to do was educate women.”

Courtesy of University of Pennsylvania

Courtesy of University of PennsylvaniaIn many of Dickens’s medical pursuits, she had been honoured as the first. Now, she would see to it that she wasn’t the last. In 1969 she became Penn’s associate dean for minority affairs, recruiting more promising black and minority students to become doctors. Within five years she had increased enrollment from three to 64 minority students.

One of her recruits in the 1980s, Horace DeLisser, recalls when Dickens invited all of the incoming black students – at that point just five or six – into her home before the start of classes. He remembers “her stature, and this coming together of a group of students who would be our own little community”. DeLisser, a pulmonary doctor, now occupies Dickens’s former position as the school’s associate dean for diversity and inclusion.

Another Penn graduate, Florencia Greer Polite, says that when she and the other medical students first met Dickens in the 1990s, “we knew we were in the midst of OB royalty”. But it was only after Polite returned as the current head of the Teen Clinic, now named the Helen O Dickens Center for Women’s Health, that she learned the extent of Dickens’s trailblazing career.

“She created doors where doors were not there,” says Polite. “There was no doubt she was a revolutionary.”

Dickens herself would have eschewed such terms. But Gamble, too, says she looked to Dickens throughout her career as an example of a “quiet activist”.

“I’m not sure whether she considered herself that, but it’s definitely what came across to those of us that she mentored,” she says. “She might not have been on the picket lines, but she always worked to advance the health of black women.”

Ask people to imagine a scientist, and many of us will picture the same thing – a heterosexual white male. Historically, a number of challenges have made it much more difficult for those who don’t fit that stereotype to enter fields like science, math or engineering.

There are, however, many individuals from diverse backgrounds who have shaped our understanding of life and the Universe, but whose stories have gone untold – until now. With our new BBC Future column, we are celebrating the “missed geniuses” who made the world what it is today.

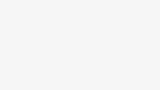

Portrait of Helen O Dickens by Emmanuel Lafont.

Source link